Note

Click here to download the full example code

Plugins and hybrid computation¶

Author: Josh Izaac — Posted: 11 October 2019. Last updated: 01 February 2021.

This tutorial introduces the notion of hybrid computation by combining several PennyLane plugins. We first introduce PennyLane’s Strawberry Fields plugin and use it to explore a non-Gaussian photonic circuit. We then combine this photonic circuit with a qubit circuit — along with some classical processing — to create and optimize a fully hybrid computation. Be sure to read through the introductory qubit rotation and Gaussian transformation tutorials before attempting this tutorial.

Warning

This demo is only compatible with PennyLane version 0.29 or below.

Note

To follow along with this tutorial on your own computer, you will require the PennyLane-SF plugin, in order to access the Strawberry Fields Fock backend using PennyLane. It can be installed via pip:

pip install pennylane-sf

A non-Gaussian circuit¶

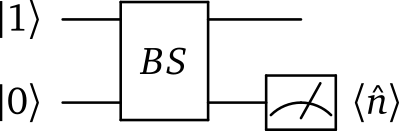

We first consider a photonic circuit which is similar in spirit to the qubit rotation circuit:

Breaking this down, step-by-step:

We start the computation with two qumode subsystems. In PennyLane, we use the shorthand ‘wires’ to refer to quantum subsystems, whether they are qumodes, qubits, or any other kind of quantum register.

Prepare the state \(\left|1,0\right\rangle\). That is, the first wire (wire 0) is prepared in a single-photon state, while the second wire (wire 1) is prepared in the vacuum state. The former state is non-Gaussian, necessitating the use of the

'strawberryfields.fock'backend device.Both wires are then incident on a beamsplitter, with free parameters \(\theta\) and \(\phi\). Here, we have the convention that the beamsplitter transmission amplitude is \(t=\cos\theta\), and the reflection amplitude is \(r=e^{i\phi}\sin\theta\). See Quantum operators for a full list of operation conventions.

Finally, we measure the mean photon number \(\left\langle \hat{n}\right\rangle\) of the second wire, where

\[\hat{n} = \hat{a}^{\dagger}\hat{a}\]is the number operator, acting on the Fock basis number states, such that \(\hat{n}\left|n\right\rangle = n\left|n\right\rangle\).

The aim of this tutorial is to optimize the beamsplitter parameters \((\theta, \phi)\) such that the expected photon number of the second wire is maximized. Since the beamsplitter is a passive optical element that preserves the total photon number, this to the output state \(\left|0,1\right\rangle\) — i.e., when the incident photon from the first wire has been ‘redirected’ to the second wire.

Exact calculation¶

To compare with later numerical results, we can first consider what happens analytically. The initial state of the circuit is \(\left|\psi_0\right\rangle=\left|1,0\right\rangle\), and the output state of the system is of the form \(\left|\psi\right\rangle = a\left|1, 0\right\rangle + b\left|0,1\right\rangle\), where \(|a|^2+|b|^2=1\). We may thus write the output state as a vector in this computational basis, \(\left|\psi\right\rangle = \begin{bmatrix}a & b\end{bmatrix}^T\).

The beamsplitter acts on this two-dimensional subspace as follows:

Furthermore, the mean photon number of the second wire is

Therefore, we can see that:

\(0\leq \left\langle \hat{n}_1\right\rangle\leq 1\): the output of the quantum circuit is bound between 0 and 1;

\(\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi} \left\langle \hat{n}_1\right\rangle=0\): the output of the quantum circuit is independent of the beamsplitter phase \(\phi\);

The output of the quantum circuit above is maximised when \(\theta=(2m+1)\pi/2\) for \(m\in\mathbb{Z}_0\).

Loading the plugin device¶

While PennyLane provides a basic qubit simulator ('default.qubit') and a basic CV

Gaussian simulator ('default.gaussian'), the true power of PennyLane comes from its

plugin ecosystem, allowing quantum computations

to be run on a variety of quantum simulator and hardware devices.

For this circuit, we will be using the 'strawberryfields.fock' device to construct

a QNode. This allows the underlying quantum computation to be performed using the

Strawberry Fields Fock backend.

As usual, we begin by importing PennyLane and the wrapped version of NumPy provided by PennyLane:

import pennylane as qml

from pennylane import numpy as np

Next, we create a device to run the quantum node. This is easy in PennyLane; as soon as

the PennyLane-SF plugin is installed, the 'strawberryfields.fock' device can be loaded

— no additional commands or library imports required.

dev_fock = qml.device("strawberryfields.fock", wires=2, cutoff_dim=2)

Compared to the default devices provided with PennyLane, the 'strawberryfields.fock'

device requires the additional keyword argument:

cutoff_dim: the Fock space truncation used to perform the quantum simulation

Note

Devices provided by external plugins may require additional arguments and keyword arguments — consult the plugin documentation for more details.

Constructing the QNode¶

Now that we have initialized the device, we can construct our quantum node. Like

the other tutorials, we use the qnode decorator

to convert our quantum function (encoded by the circuit above) into a quantum node

running on Strawberry Fields.

@qml.qnode(dev_fock, diff_method="parameter-shift")

def photon_redirection(params):

qml.FockState(1, wires=0)

qml.Beamsplitter(params[0], params[1], wires=[0, 1])

return qml.expval(qml.NumberOperator(1))

The 'strawberryfields.fock' device supports all CV objects provided by PennyLane;

see CV operations.

Optimization¶

Let’s now use one of the built-in PennyLane optimizers in order to carry out photon redirection. Since we wish to maximize the mean photon number of the second wire, we can define our cost function to minimize the negative of the circuit output.

def cost(params):

return -photon_redirection(params)

To begin our optimization, let’s choose the following small initial values of \(\theta\) and \(\phi\):

init_params = np.array([0.01, 0.01], requires_grad=True)

print(cost(init_params))

Out:

-9.999666671111081e-05

Here, we choose the values of \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) to be very close to zero; this results in \(B(\theta,\phi)\approx I\), and the output of the quantum circuit will be very close to \(\left|1, 0\right\rangle\) — i.e., the circuit leaves the photon in the first mode.

Why don’t we choose \(\theta=0\) and \(\phi=0\)?

At this point in the parameter space, \(\left\langle \hat{n}_1\right\rangle = 0\), and \(\frac{d}{d\theta}\left\langle{\hat{n}_1}\right\rangle|_{\theta=0}=2\sin\theta\cos\theta|_{\theta=0}=0\). Since the gradient is zero at those initial parameter values, the optimization algorithm would never descend from the maximum.

This can also be verified directly using PennyLane:

dphoton_redirection = qml.grad(photon_redirection, argnum=0)

print(dphoton_redirection([0.0, 0.0]))

Out:

[array(0.), array(0.)]

Now, let’s use the GradientDescentOptimizer, and update the circuit

parameters over 100 optimization steps.

# initialise the optimizer

opt = qml.GradientDescentOptimizer(stepsize=0.4)

# set the number of steps

steps = 100

# set the initial parameter values

params = init_params

for i in range(steps):

# update the circuit parameters

params = opt.step(cost, params)

if (i + 1) % 5 == 0:

print("Cost after step {:5d}: {: .7f}".format(i + 1, cost(params)))

print("Optimized rotation angles: {}".format(params))

Out:

Cost after step 5: -0.0349558

Cost after step 10: -0.9969017

Cost after step 15: -1.0000000

Cost after step 20: -1.0000000

Cost after step 25: -1.0000000

Cost after step 30: -1.0000000

Cost after step 35: -1.0000000

Cost after step 40: -1.0000000

Cost after step 45: -1.0000000

Cost after step 50: -1.0000000

Cost after step 55: -1.0000000

Cost after step 60: -1.0000000

Cost after step 65: -1.0000000

Cost after step 70: -1.0000000

Cost after step 75: -1.0000000

Cost after step 80: -1.0000000

Cost after step 85: -1.0000000

Cost after step 90: -1.0000000

Cost after step 95: -1.0000000

Cost after step 100: -1.0000000

Optimized rotation angles: [1.57079633 0.01 ]

Comparing this to the exact calculation above, this is close to the optimum value of \(\theta=\pi/2\), while the value of \(\phi\) has not changed — consistent with the fact that \(\left\langle \hat{n}_1\right\rangle\) is independent of \(\phi\).

Hybrid computation¶

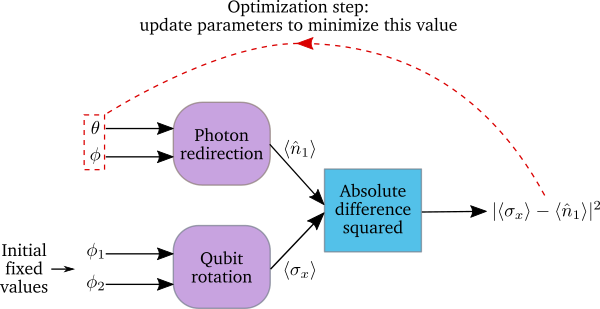

To really highlight the capabilities of PennyLane, let’s now combine the qubit-rotation QNode from the qubit rotation tutorial with the CV photon-redirection QNode from above, as well as some classical processing, to produce a truly hybrid computational model.

First, we define a computation consisting of three steps: two quantum nodes (the qubit rotation

and photon redirection circuits, running on the 'default.qubit' and

'strawberryfields.fock' devices, respectively), along with a classical function, that simply

returns the squared difference of its two inputs using NumPy:

# create the devices

dev_qubit = qml.device("default.qubit", wires=1)

dev_fock = qml.device("strawberryfields.fock", wires=2, cutoff_dim=10)

@qml.qnode(dev_qubit, interface="autograd")

def qubit_rotation(phi1, phi2):

"""Qubit rotation QNode"""

qml.RX(phi1, wires=0)

qml.RY(phi2, wires=0)

return qml.expval(qml.PauliZ(0))

@qml.qnode(dev_fock, diff_method="parameter-shift")

def photon_redirection(params):

"""The photon redirection QNode"""

qml.FockState(1, wires=0)

qml.Beamsplitter(params[0], params[1], wires=[0, 1])

return qml.expval(qml.NumberOperator(1))

def squared_difference(x, y):

"""Classical node to compute the squared

difference between two inputs"""

return np.abs(x - y) ** 2

Now, we can define an objective function associated with the optimization, linking together our three subcomponents. Here, we wish to perform the following hybrid quantum-classical optimization:

The qubit-rotation circuit will contain fixed rotation angles \(\phi_1\) and \(\phi_2\).

The photon-redirection circuit will contain two free parameters, the beamsplitter angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\), which are to be optimized.

The outputs of both QNodes will then be fed into the classical node, returning the squared difference of the two quantum functions.

Finally, the optimizer will calculate the gradient of the entire computation with respect to the free parameters \(\theta\) and \(\phi\), and update their values.

In essence, we are optimizing the photon-redirection circuit to return the same expectation value as the qubit-rotation circuit, even though they are two completely independent quantum systems.

We can translate this computational graph to the following function, which combines the three nodes into a single hybrid computation. Below, we choose default values \(\phi_1=0.5\), \(\phi_2=0.1\):

def cost(params, phi1=0.5, phi2=0.1):

"""Returns the squared difference between

the photon-redirection and qubit-rotation QNodes, for

fixed values of the qubit rotation angles phi1 and phi2"""

qubit_result = qubit_rotation(phi1, phi2)

photon_result = photon_redirection(params)

return squared_difference(qubit_result, photon_result)

Now, we use the built-in GradientDescentOptimizer to perform the optimization

for 100 steps. As before, we choose initial beamsplitter parameters of

\(\theta=0.01\), \(\phi=0.01\).

# initialise the optimizer

opt = qml.GradientDescentOptimizer(stepsize=0.4)

# set the number of steps

steps = 100

# set the initial parameter values

params = np.array([0.01, 0.01], requires_grad=True)

for i in range(steps):

# update the circuit parameters

params = opt.step(cost, params)

if (i + 1) % 5 == 0:

print("Cost after step {:5d}: {: .7f}".format(i + 1, cost(params)))

print("Optimized rotation angles: {}".format(params))

Out:

Cost after step 5: 0.2154539

Cost after step 10: 0.0000982

Cost after step 15: 0.0000011

Cost after step 20: 0.0000000

Cost after step 25: 0.0000000

Cost after step 30: 0.0000000

Cost after step 35: 0.0000000

Cost after step 40: 0.0000000

Cost after step 45: 0.0000000

Cost after step 50: 0.0000000

Cost after step 55: 0.0000000

Cost after step 60: 0.0000000

Cost after step 65: 0.0000000

Cost after step 70: 0.0000000

Cost after step 75: 0.0000000

Cost after step 80: 0.0000000

Cost after step 85: 0.0000000

Cost after step 90: 0.0000000

Cost after step 95: 0.0000000

Cost after step 100: 0.0000000

Optimized rotation angles: [1.20671364 0.01 ]

Substituting this into the photon redirection QNode shows that it now produces the same output as the qubit rotation QNode:

result = [1.20671364, 0.01]

print(photon_redirection(result))

print(qubit_rotation(0.5, 0.1))

Out:

0.8731983021146449

0.8731983044562817

This is just a simple example of the kind of hybrid computation that can be carried out in PennyLane. Quantum nodes (bound to different devices) and classical functions can be combined in many different and interesting ways.