Note

Click here to download the full example code

Using JAX with PennyLane¶

Author: Chase Roberts — Posted: 12 April 2021. Last updated: 12 April 2021.

JAX is an incredibly powerful scientific computing library that has been gaining traction in both the physics and deep learning communities. While JAX was originally designed for classical machine learning (ML), many of its transformations are also useful for quantum machine learning (QML), and can be used directly with PennyLane.

In this tutorial, we’ll go over a number of JAX transformations and show how you can

use them to build and optimize quantum circuits. We’ll show examples of how to

do gradient descent with jax.grad, run quantum circuits in parallel

using jax.vmap, compile and optimize simulations with jax.jit,

and control and seed the random nature of quantum computer simulations

with jax.random. By the end of this tutorial you should feel just as comfortable

transforming quantum computing programs with JAX as you do transforming your

neural networks.

If this is your first time reading PennyLane code, we recommend going through the basic tutorial first. It’s all in vanilla NumPy, so you should be able to easily transfer what you learn to JAX when you come back.

With that said, we begin by importing PennyLane, JAX, the JAX-provided version of NumPy and

set up a two-qubit device for computations. We’ll be using the default.qubit device

for the first part of this tutorial.

# Added to silence some warnings.

from jax.config import config

config.update("jax_enable_x64", True)

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

import pennylane as qml

dev = qml.device("default.qubit", wires=2)

Let’s start with a simple example circuit that generates a two-qubit entangled state, then evaluates the expectation value of the Pauli-Z operator on the first wire.

@qml.qnode(dev, interface="jax")

def circuit(param):

# These two gates represent our QML model.

qml.RX(param, wires=0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

# The expval here will be the "cost function" we try to minimize.

# Usually, this would be defined by the problem we want to solve,

# but for this example we'll just use a single PauliZ.

return qml.expval(qml.PauliZ(0))

Out:

No GPU/TPU found, falling back to CPU. (Set TF_CPP_MIN_LOG_LEVEL=0 and rerun for more info.)

We can now execute the circuit just like any other python function.

print(f"Result: {repr(circuit(0.123))}")

Out:

Result: Array(0.99244503, dtype=float64)

Notice that the output of the circuit is a JAX DeviceArray.

In fact, when we use the default.qubit device, the entire computation

is done in JAX, so we can use all of the JAX tools out of the box!

Now let’s move on to an example of a transformation. The code we wrote above is entirely

differentiable, so let’s calculate its gradient with jax.grad.

print("\nGradient Descent")

print("---------------")

# We use jax.grad here to transform our circuit method into one

# that calcuates the gradient of the output relative to the input.

grad_circuit = jax.grad(circuit)

print(f"grad_circuit(jnp.pi / 2): {grad_circuit(jnp.pi / 2):0.3f}")

# We can then use this grad_circuit function to optimize the parameter value

# via gradient descent.

param = 0.123 # Some initial value.

print(f"Initial param: {param:0.3f}")

print(f"Initial cost: {circuit(param):0.3f}")

for _ in range(100): # Run for 100 steps.

param -= grad_circuit(param) # Gradient-descent update.

print(f"Tuned param: {param:0.3f}")

print(f"Tuned cost: {circuit(param):0.3f}")

Out:

Gradient Descent

---------------

grad_circuit(jnp.pi / 2): -1.000

Initial param: 0.123

Initial cost: 0.992

Tuned param: 3.142

Tuned cost: -1.000

And that’s QML in a nutshell! If you’ve done classical machine learning before, the above training loop should feel very familiar to you. The only difference is that we used a quantum computer (or rather, a simulation of one) as part of our model and cost calculation. In the end, almost all QML problems involve tuning some parameters and minimizing some cost function, just like classical ML. While classical ML focuses on learning classical systems like language or vision, QML is most useful for learning about quantum systems. For example, finding chemical ground states or learning to sample thermal energy states.

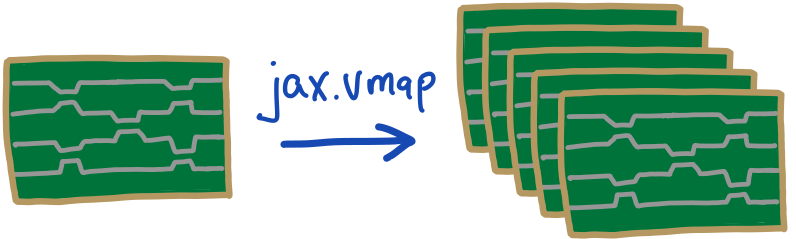

Batching and Evolutionary Strategies¶

We just showed how we can use gradient methods to learn a parameter value,

but on real quantum computing hardware, calculating gradients can be really expensive and noisy.

Another approach is to use evolutionary strategies

(ES) to learn these parameters.

Here, we will be using the jax.vmap transform

to make running batches of circuits much easier. vmap essentially transforms a single quantum computer into

multiple running in parallel!

print("\n\nBatching and Evolutionary Strategies")

print("------------------------------------")

# Create a vectorized version of our original circuit.

vcircuit = jax.vmap(circuit)

# Now, we call the ``vcircuit`` with multiple parameters at once and get back a

# batch of expectations.

# This examples runs 3 quantum circuits in parallel.

batch_params = jnp.array([1.02, 0.123, -0.571])

batched_results = vcircuit(batch_params)

print(f"Batched result: {batched_results}")

Out:

Batching and Evolutionary Strategies

------------------------------------

Batched result: [0.52336595 0.99244503 0.84136092]

Let’s now set up our ES training loop. The idea is pretty simple. First, we calculate the expected values of each of our parameters. The cost values then determine the “weight” of that example. The lower the cost, the larger the weight. These batches are then used to generate a new set of parameters.

# Needed to do randomness with JAX.

# For more info on how JAX handles randomness, see the documentation.

# https://jax.readthedocs.io/en/latest/jax.random.html

key = jax.random.PRNGKey(0)

# Generate our first set of samples.

params = jax.random.normal(key, (100,))

mean = jnp.average(params)

var = 1.0

print(f"Initial value: {mean:0.3f}")

print(f"Initial cost: {circuit(mean):0.3f}")

for _ in range(200):

# In this line, we run all 100 circuits in parallel.

costs = vcircuit(params)

# Use exp(-x) here since the costs could be negative.

weights = jnp.exp(-costs)

mean = jnp.average(params, weights=weights)

# We decrease the variance as we converge to a solution.

var = var * 0.97

# Split the PRNGKey to generate a new set of random samples.

key, split = jax.random.split(key)

params = jax.random.normal(split, (100,)) * var + mean

print(f"Final value: {mean:0.3f}")

print(f"Final cost: {circuit(mean):0.3f}")

Out:

Initial value: -0.078

Initial cost: 0.997

Final value: -3.139

Final cost: -1.000

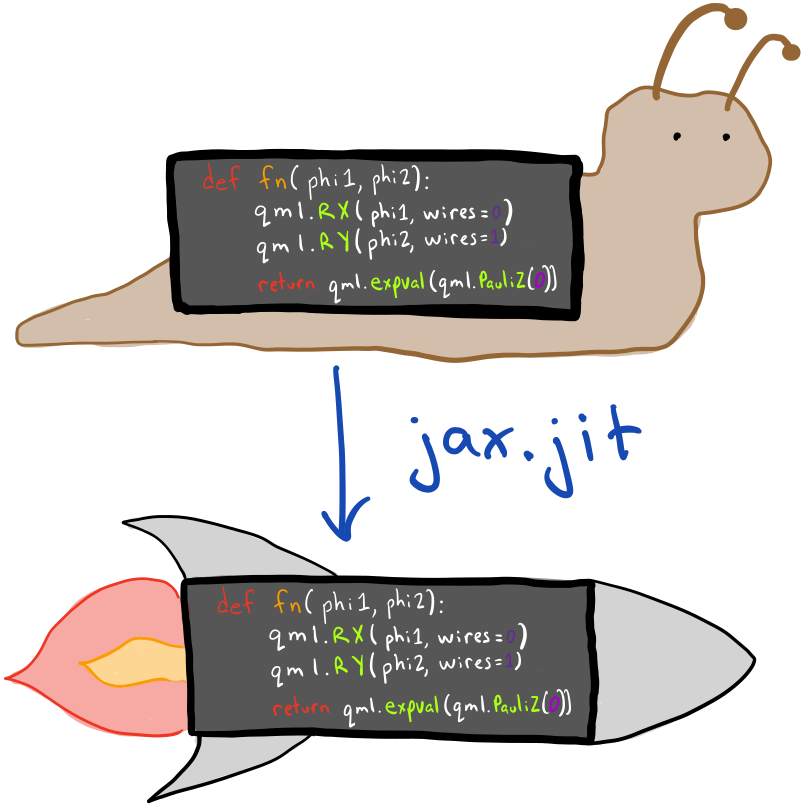

How to use jax.jit: Compiling Circuit Execution¶

JAX is built on top of XLA, a powerful

numerics library that can optimize and cross compile computations to different hardware,

including CPUs, GPUs, etc. JAX can compile its computation to XLA via the jax.jit

transform.

When compiling an XLA program, the compiler will do several rounds of optimization passes to enhance the performance of the computation. Because of this compilation overhead, you’ll generally find the first time calling the function to be slow, but all subsequent calls are much, much faster. You’ll likely want to do it if you’re running the same circuit over and over but with different parameters, like you would find in almost all variational quantum algorithms.

print("\n\nJit Example")

print("-----------")

@qml.qnode(dev, interface="jax")

def circuit(param):

qml.RX(param, wires=0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

return qml.expval(qml.PauliZ(0))

# Compiling your circuit with JAX is very easy, just add jax.jit!

jit_circuit = jax.jit(circuit)

import time

# No jit.

start = time.time()

# JAX runs async, so .block_until_ready() blocks until the computation

# is actually finished. You'll only need to use this if you're doing benchmarking.

circuit(0.123).block_until_ready()

no_jit_time = time.time() - start

# First call with jit.

start = time.time()

jit_circuit(0.123).block_until_ready()

first_time = time.time() - start

# Second call with jit.

start = time.time()

jit_circuit(0.123).block_until_ready()

second_time = time.time() - start

print(f"No jit time: {no_jit_time:0.4f} seconds")

# Compilation overhead will make the first call slower than without jit...

print(f"First run time: {first_time:0.4f} seconds")

# ... but the second run time is >100x faster than the first!

print(f"Second run time: {second_time:0.4f} seconds")

# You can see that for the cost of some compilation overhead, we can

# greatly increase our performance of our simulation by orders of magnitude.

Out:

Jit Example

-----------

No jit time: 0.0045 seconds

First run time: 0.0663 seconds

Second run time: 0.0000 seconds

Shots and Sampling with JAX¶

JAX was designed to enable experiments to be as repeatable as possible. Because of this, JAX requires us to seed all randomly generated values (as you saw in the above batching example). Sadly, the universe doesn’t allow us to seed real quantum computers, so if we want our JAX to mimic a real device, we’ll have to handle randomness ourselves.

To learn more about how JAX handles randomness, visit their documentation site.

Note

This example only applies if you are using jax.jit. Otherwise, PennyLane

automatically seeds and resets the random-number-generator for you on each call.

To set the random number generating key, you’ll have to pass the jax.random.PRNGKey

when constructing the device. Because of this, if you want to use jax.jit with randomness,

the device construction will have to happen within that jitted method.

print("\n\nRandomness")

print("----------")

# Let's create our circuit with randomness and compile it with jax.jit.

@jax.jit

def circuit(key, param):

# Notice how the device construction now happens within the jitted method.

# Also note the added '.jax' to the device path.

dev = qml.device("default.qubit.jax", wires=2, shots=10, prng_key=key)

# Now we can create our qnode within the circuit function.

@qml.qnode(dev, interface="jax", diff_method=None)

def my_circuit():

qml.RX(param, wires=0)

qml.CNOT(wires=[0, 1])

return qml.sample(qml.PauliZ(0))

return my_circuit()

key1 = jax.random.PRNGKey(0)

key2 = jax.random.PRNGKey(1)

# Notice that the first two runs return exactly the same results,

print(f"key1: {circuit(key1, jnp.pi/2)}")

print(f"key1: {circuit(key1, jnp.pi/2)}")

# The second run has different results.

print(f"key2: {circuit(key2, jnp.pi/2)}")

Out:

Randomness

----------

key1: [ 1 -1 -1 -1 1 -1 -1 -1 1 1]

key1: [ 1 -1 -1 -1 1 -1 -1 -1 1 1]

key2: [-1 -1 -1 -1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1]

Closing Remarks¶

By now, using JAX with PennyLane should feel very natural. They complement each other very nicely; JAX with its powerful transforms, and PennyLane with its easy access to quantum computers. We’re still in early days of development, but we hope to continue to grow our ecosystem around JAX, and by extension, grow JAX into quantum computing and quantum machine learning. The future looks bright for this field, and we’re excited to see what you build!